We need a serious public conversation about AI and the future of the UK

Artificial Intelligence is advancing rapidly, reshaping the foundations of economic value, social life, and national power. For us in the UK, we have a choice: allow this transformation to be shaped elsewhere and imposed on us - or decide, collectively and deliberately, what kind of AI future we want to build.

Here, I argue for an intentional, public mission for AI in the UK that prioritises broad-based economic prosperity, democratic legitimacy, and long-term social wellbeing. We need urgent action to address dependencies on foreign technology providers and to prepare for the deep structural shifts AI will bring to work, education, taxation, and creative value.

Today’s economic assumptions of widespread employment, tax-funded public services, and the commercial value of human knowledge and creativity - are all under pressure. As AI is replacing office and administrative tasks and absorbing entire knowledge domains, we must ask: What happens when many existing jobs lose economic value? Is our current education system preparing people for the world ahead? And if labour incomes shrink, where will the public purse find its future revenue? Further ahead, labour disruption is likely to extend to skilled and manual jobs as advanced robotics, imbued with AI, spread in the economy.

At the same time, the way AI is built today concentrates economic power in a handful of players. Most commercial models rely on scraping public data, including the work of writers, creatives, and publishers, without consent or compensation. The value flows disproportionately to a handful of large foreign firms. A different model is possible: one where AI is trained with consent and creators are compensated and benefits are shared across our economy. Recent efforts such as Switzerland’s public LLM developed by ETH Zürich and EPFL and startups like Pleias in France show what a more democratic AI economy could look like.

I don’t have any magic prescriptions. Instead, I pose questions that we must confront through public dialogue, inclusive policymaking, and a clear-eyed vision for our collective future.

Note on security and existential risks: I believe there is a real risk from future uncontrolled AI development to our national security and greater existential risks to humanity. This is a serious issue that warrants serious attention and global cooperation to ensure AI development is safe and responsible. It is however a distinct issue from what appears to be inevitable economic and social disruption from today’s AI systems.

1. Work, Education and the Disruption of Economic Value

We are starting to see the impact of AI on the labour market. It's likely that current changes in hiring patterns will accelerate, affecting a greater variety of jobs across the economy. Critically, our education system, designed for a pre-AI world, may be unfit for the challenges ahead.

What is happening to entry-level jobs?

Recent data suggest sharp declines in opportunities for new entrants:

Entry-level job postings in the UK have fallen by over 30% since the launch of ChatGPT (Adzuna, via The Guardian, June 2025).

Graduate job openings are at their lowest level since 2018 (Financial Times, June 2025).

Tasks across many sectors are increasingly exposed to automation. Modeling future impact on job leads to significantly varying results, depending on the assumptions. For example The Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) projects:

A worst case scenario of 8 million UK jobs may be at risk if AI deployment is not actively managed and;

A best case scenario where AI augments rather than replaces jobs, and leads to 13% increase in GDP with no job losses.

Which jobs will still matter, and which won’t?

Fields built on junior-level analysis, content production, such as media, law, research, finance, administration and design face particular pressure. Entry-level roles in sectors like coding may no longer be needed. This raises pressing questions:

What happens to workforce development when the early rungs of the career ladder disappear?

And this is just the start

LLMs, generative AI and AI as a software tool are not the end of the road. We would be making a big disservice to ourselves if we did not anticipate what might come next. There are two important directions we need to think about:

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)

The AI research community is divided over whether LLMs can lead to AGI or not, but less about whether we will eventually have AGI through a combination of different AI approaches. The important question here is not about whether AI achieves what we would recognize as consciousness or true intelligence, rather the ability of AI to undertake a growing number of tasks with sufficient proficiency to replace people.

Generative AI tools have already demonstrated capacity to expand into new and more complex use cases. The combination of more versatile models, engineering improvements and product capability will continue to produce big gains, regardless of any new fundamental breakthroughs in LLMs.

And there is significant R&D going into new AI methods that could, over the coming 3–5 years, lead to another leap in AI and a new wave of job replacement. For example, Yann LeCun's lab at Meta is exploring novel architectures such as joint embedding predictive architecture (JEPA), which aim to move beyond LLMs toward systems that better understand physical reality. The neurosymbolic approach long championed by Gary Marcus could be another.

Robotics and embodied AI

There are strong signs that the field of robotics is nearing a breakthrough and recent demonstrations from Boston Dynamics and others suggest accelerating progress. 2025 feels similar to where AI was in 2017, when the Transformer paper emerged: the foundations of a major change have been laid, and within a few years we could see robots proliferate widely across society.

We’ve had static robots in our economy for a long time, particularly in manufacturing. They, like the robots we today see cleaning train stations or mowing lawns, are very limited in the types of manual jobs they can replace - they can undertake very narrowly-defined tasks and are space-bound to a very specific environment.

The best evidence of this changing are self-driving cars, which are finally starting to become viable: these are robots with AI on wheels. The integration of LLMs will make their interactive capabilities and robotic nature much more apparent. But the next major shift will come from humanoid robots that can navigate our world. These have advanced considerably in terms of mobility, manipulation, and environmental awareness, driven by improvements in both mechanical design and onboard AI.

Companies like Tesla, Figure, Unitree and Agility Robotics are racing to develop general-purpose humanoid platforms intended to handle logistics, warehousing, retail and elder care. As with AI, China and the USA are the clear leaders in this race. It’s worth noting here that NVIDIA, arguably the most important company in AI, has significantly increased its investment and focus on robotics, with its Jetson and Isaac platforms being widely adopted to power next-generation humanoid and industrial robots.

The trajectory suggests that robots capable of performing a wide range of physical tasks could enter the economy within the next few years, and usher in a new wave of labour displacement in hospitality, retail, logistics and other sectors. There will be a range of complex safety and liability to contend with, which may slow down adoption - but there should be no doubt: the robots are coming.

Is our educational system fit for purpose?

At the best of times educational curricula evolve slowly. This is a very big problem when things are changing as rapidly as they are. Some of today’s university degrees and vocational training may no longer lead to gainful employment. The core question becomes:

How can we design an education system flexible enough to keep pace with these shifts?

2. AI and the Economic Foundations of the State

A model built on labour income

Income tax and National Insurance account for ~ 46% of UK tax revenues, the remainder comes from VAT, corporate, council and other taxes. Our public services assumes high employment, steady wage growth and healthy tax revenues. AI could disrupt all three.

What fiscal strategies might become necessary as automation scales?

Is AI redistributing value upward and offshore?

Most general-purpose AI models are built by US and Chinese firms, using public data scraped globally, and monetised through subscriptions and APIs. The UK is exporting intellectual and cultural value while receiving little in return.

We have several successful AI companies but these are almost all operating in discreet AI applications (not general purpose AI) or at the product layer, dependent on foreign general purpose model developers.

Despite the UK having one of the strongest AI research capacities in the world, there isn’t a single private British AI frontier lab.

The crown jewel of the UK’s AI industry is Google Deepmind, a company sadly owned by… Google, which in turn owns all its IP and world class research. Allowing the sale of Deepmind was probably the single biggest failure of technology policy made by a British government in the (with the sale of ARM a close second).

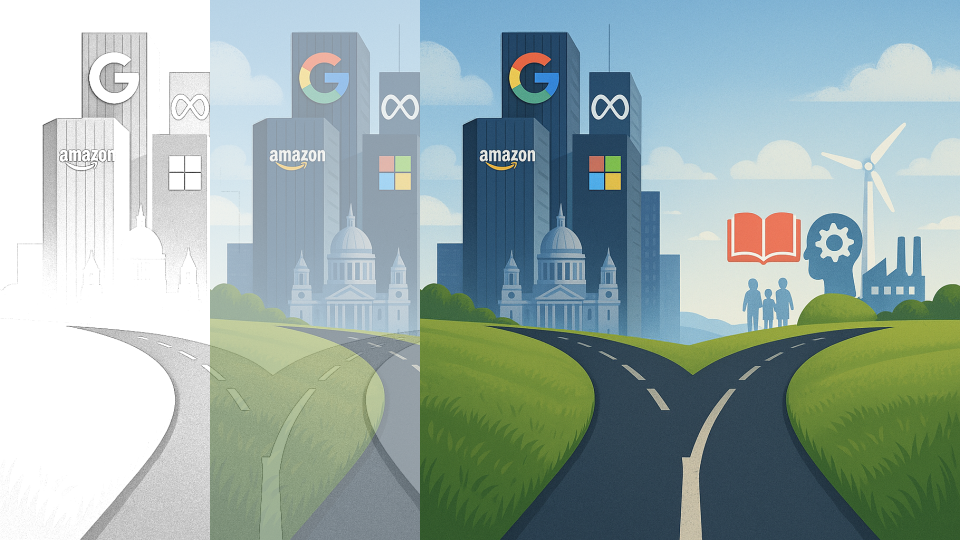

The history of the past 25 years tells us where this will go. The vast majority of profits accruing to the large platform owners, whilst everyone else battles for scraps. And AI is a general purpose technology that will be pervasive across all sectors of the economy, not just tech.

If we let the same scenario unfold again we will be left with an even greater concentration of economic and political power in the hands of a few foreign companies - all while grappling with high unemployment and social upheaval.

The British government is making a big bet with its plan to “mainline AI in the veins” of the economy. It’s clear that AI can massively increase individual and organizational productivity but -

if you only need half the number of people, or even a third, to produce ore - will that result in a more prosperous UK?

This is a rhetorical question because, of course not. But this is the path we’re on.

The government’s approach to AI so far has been to sign deals with the US AI giants, including Open AI, Google and Anthropic. This continues a long tradition of handing over public contracts worth billions of pounds to US tech companies with no real vision of how to grow our own domestic competitors.

3. How We Can Do AI Better: Data, Consent, and Economic Growth

Could new models of ownership, licensing, procurement or infrastructure help reverse this trend? How should we define and capture value in an economy where human labour is no longer the primary engine of growth? How do we make AI work for the British people and the British economy?

Most large models are trained on unlicensed data scraped from websites, books and code repositories. Yet only a few companies profit from this infrastructure. Generative AI now competes with creators by mimicking their styles, outputs, and ideas. So far, the government has decided that throwing the UK’s creative industry under the bus is the only path to leveraging the potential of AI. Their thinking is that if we do something that slows down the AI industry, we will lose out.

But that betrays a lack of imagination. And a hell of a lot of lobbying from the big American AI companies

What if AI models share revenue with copyright owners?

AI companies are already making licensing deals with publishers - including the Guardian and the FT. Why not the same with the creative sector? Likely because they need access to the new information that news publishers produce every day, whilst having already trained their models on all the art, music and books they could get their hands on, they don’t really need all the newer works.

There is no technical barrier to having models that compensate copyright owners, but it will mean that AI model developers make less money and share the economic benefits with the people who produced the data that powers the models.

A world where copyrighted is respected and a handful of AI companies achieve trillion dollar valutations may not be achievable but a world where there is both a fairer distribution of revenues and more companies worth many billions of pounds is very possible.

Should we really be undermining our creative sector to help create trillion dollar companies in the US that pay very little tax here?

No

Should we develop AI as a public good?

Other countries are doing this. The leading Swiss universities - ETH Zurich and EPFL - are about to release an open source Swiss public LLM trained on the “Alps” supercomputer at the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre.

Should the UK develop public foundation models to serve education, public health and civil service functions - as well as provide a foundation for British AI companies to build on?

Can we direct public procurement to grow British competition?

We don’t have a British product that can replace ChatGPT, Gemini or Claude today, but that doesn’t mean we couldn’t in the future. Directing a portion of AI public procurement budgets to British solutions could go a long way. Given how much money the government spends on these contracts, reserving say 30% of this expenditure for British AI companies would amount to hundreds of millions of pounds, or more, over the next few years.

France, for example, seems to be taking a much more serious steps to support its domestic AI industry and is already home to companies like two of the top global startups in AI development: Hugging Face and Mistral, as well as exciting challengers like Pleias who are pioneering a wave of smaller, specialized and ethically trained models.

We can all be proud that DeepMind is built on British science, research and academia. But the fruit of all that British excellence is now flowing to a US company.

But it won't be enough

Even with fairer distribution of AI revenues, this will not prevent economic and job disruption. The internet changed some industries forever - from travel agents to music, TV and journalism. AI and robotics will bring bigger changes to more industries. They will survive but in very different forms and the transition will be painful.

How can we support the industries most affected by AI through this transition?

If a large proportion of work is undertaken by AI systems and robots, can we still rely on the same balance of income v corporate tax? Should there be a new kind of taxation for AI or robot workers? The tax system was designed for a world where humans were the workers, increasingly this will be a mix of people, AI and robots and taxation must adapt.

Should we have special levies on certain types of AI systems, akin to an income tax?

4. We need a Public Conversation on AI and the UK’s Future.

What kind of economic and social future do we want?

How do we educate for adaptability, not redundancy?

What counts as a fair distribution of AI's gains?

Who gets to shape the digital infrastructure of our country?

AI represents much more than a technology shift. It’s economic, societal and political. The choices we make today will determine whether AI strengthens or fragments the UK’s social and economic fabric.

We have to shape our future as a country, not let be imposed on us. We need to start an open, frank public conversation - urgently.